Will Later Starts Really Make Up For Lost ZZZs?

February 18, 2020

High school is notorious for handing out excessive amounts of homework, inducing stress, and negatively affecting sleep. Some argue that it’s all part of the experience. That all of high school’s challenges prepare students for a fast paced and demanding real world. And that may be true. But teenagers are not adults. They are still developing and a good night’s sleep is vital for their well being.

High school is notorious for handing out excessive amounts of homework, inducing stress, and negatively affecting sleep. Some argue that it’s all part of the experience. That all of high school’s challenges prepare students for a fast paced and demanding real world. And that may be true. But teenagers are not adults. They are still developing and a good night’s sleep is vital for their well being.

In hopes of boosting teen performance at school by allowing for a better night’s sleep, California will soon require its high schools to start no earlier than 8:30 AM and its middle schools to start no earlier than 8:00 AM. This does not apply to zero period classes.

The El Monte Union High School District expects to change their start times to 8:30 for the 2022-2023 school year. Dr. Edward Zuniga, EMUHSD Superintendent, explained that the district cannot change the start times until its contract with the teachers ends.

The change comes in light of evidence linked to the circadian biological clocks of teenagers. The National Sleep Foundation (NSF) found that “teens’ natural sleep cycle puts them in conflict with school start times.”

The change comes in light of evidence linked to the circadian biological clocks of teenagers. The National Sleep Foundation (NSF) found that “teens’ natural sleep cycle puts them in conflict with school start times.”

Raymond Hernandez, Arroyo social science teacher, found evidence of this clash in his own classroom, “It seems like first period is a little underperforming … because they are kind of tired [and] it’s the beginning of the day.”

Today’s average teen, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), has trouble falling asleep before 11 PM and is “best suited to wake at 8:00 AM or later.” The AAP also concluded that “optimal sleep for most teenagers is in the range of 8.5 to 9.5 hours per night.” By pushing back start times, lawmakers hope that school will no longer interfere with teens’ sleep cycles.

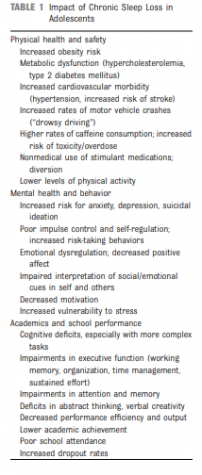

The AAP found several studies which pointed to “an association between decreased sleep duration and lower academic achievement at the middle school, high school, and college levels, as well as higher rates of absenteeism and tardiness and decreased readiness to learn.”

(Table Courtesy of the American Academy of Pediatrics)

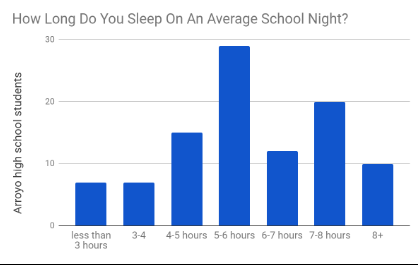

A poll conducted in November 2019 asked 100 Arroyo students how many hours of sleep they got on an average school night. The results:

A collective 90 students reported sleeping less than the recommended 8 hours.

Leyna Ho, 12, who sleeps an average of six hours this school year, attributes her lack of sleep to an excessive amount of homework, “I got the least sleep in sophomore and junior year, I remember pulling all-nighters all the time, just to finish [my homework]…[Junior year] when I barely got any sleep, it was a struggle to keep my eyes open in [my] zero period math class.”

Ho believes that pushing back the start times will help the students who have trouble falling asleep earlier, but will not impact the students who stay up all night to study.

Hernandez agrees that pushing back the start times will only affect a certain number of students, but for a different reason. “I think [pushing back the start times is] a good idea … on paper … but I don’t know if it’s going to have a huge impact on [Arroyo] students, mostly because a lot of [students] don’t drive,” said Hernandez. He pointed out that because many students rely on getting dropped off at school by a parent who works, the new law may force parents to drop their children off early, having little to no effect on the amount of time they sleep.

Dr. Zuniga added that the school is “going to have to be responsible for those students [who get dropped off early because ] … The state right now, is not funding anything to support any type of supervision or morning for kids.”

Zuniga brought up another group who might feel the adverse effects of this new law: student athletes. If school starts later, practices will too, and Zuniga expressed concern over students’ safety as the sun goes down.

“Unfortunately we only have a few lights, like at the stadium. The other practice areas [don’t] have lights,” explained Zuniga. Ho, one of many Arroyo student athletes and AP students, has often had to walk home in the dark after practice. Pushing practices later into the evening could create a safety issue for students who stay at school for extracurriculars.

Ms. Angelita Gonzales-Hernandez, Principal, brought up another factor that may undermine the law’s purpose. Later starts may lead students to “stay up later instead of going to bed earlier.” Gonzales stressed that in order for later starts to work, the school will need to “educat[e] the parents and students and [let] them understand that [they] need to better allot [their time to make sure [they] do get that sleep and not stay up late.”

The law may help students sleep more but there are other noteworthy factors that contribute to sleep deprivation. If the law’s sole purpose is to keep school times from conflicting with teenagers’ sleep cycles, then it will achieve that goal. But there is much more that comes with pushing back start times and it is difficult for one law to work for all students. “At least it benefits some people [which is] better than none,” said Ho.

Sources:

https://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/pediatrics/134/3/642.full.pdf